Thailand should not follow Sri Lanka’s lead in sanctifying a state religion.

Thailand is a warm, welcoming society. The people are friendly, dress is informal, temperatures are pleasant. Foreigners are welcome and can enjoy beautiful beaches, explore primitive countrysides, or climb challenging hills, and then retreat to first-world luxuries in Bangkok and Chiang-mai.

A Buddhist-majority society, Thailand leaves religious minorities alone. In theory, the government limits which groups can register and how many missionaries can enter, but in practice, reports the State Department: “Unregistered religious organizations operated freely, and the government’s practice of not recognizing any new religious faiths has not restricted the activities of unregistered religious groups,” or foreign missionaries.

The main limits are “laws prohibiting speech likely to insult Buddhism,” the State Department notes. Thai authorities don’t suffer national insults gladly: Foreigners have been imprisoned and deported for insulting the king, a revered figure.

Yet Bangkok’s policy of religious tolerance is coming under pressure. The forces of Buddhist nationalism have been active in the campaign over a new constitution, which culminates in a vote Sunday.

A military coup last Fall highlighted the authoritarian undercurrent in Thai politics. Supporters of the ousted government were targets of the military junta last year; next it could be minority religious faiths.

The Thai state has always been secular. The last constitution, suspended by the military, required the government to “patronize and protect Buddhism and other religions.” Christian and Muslim activities also were subsidized.

The replacement constitution may not be so ecumenical. The military has produced a more authoritarian document: The Senate would be appointed, for instance. More ominously, though the Constitution Drafting Assembly refused demands by Buddhist nationalists to make Buddhism Thailand’s official religion, they have been campaigning against the proposal as a result.

They claim their faith is at risk: “Buddhism is increasingly coming under threat,” contends Thongchai Kuasakul, who heads the Buddhists’ Network of Thailand. A Muslim insurgency in south Thailand, where Islamic fighters have targeted Buddhist monks and bombed Buddhist temples, fuels these fears.

The military originally dismissed the idea of turning Buddhism into a state religion, but a minuscule march in Bangkok — by just 4,000 people — apparently spooked the junta. The public mood has been shifting against the regime because of its mediocre economic performance and slow return to democracy. Supporters of former Prime Minister Thaksin Shinawatra, moreover, are attempting to turn the Buddhist proposal to their advantage.

So army chief Gen. Sonthi Boonyaratglin, a Muslim who heads the ruling Council for National Security, responded that he wouldn’t block an amendment turning Buddhism into the state religion. “If a stipulation in the charter to this effect would lead to peace in the country,” he said, “then it would be better to include it.”

Although the drafting committee decided against doing so, the Thai people might reject the constitution, which would send the issue back to the military regime. Moreover, the Buddhist campaign is making Muslims and Christians nervous. In the end, religious repression initiated by Buddhists doesn’t look much different than repression initiated by Muslims, or communists, or anyone else.

Some Thai observers dismiss the controversy as without substance. There is, for instance, no Buddhist equivalent to Islamic law, says Ammar Siamwalla, a Muslim economist from Bangkok. “Our constitution is the least respected document in the country. It’s been torn up too many times [17 to be exact] to be so obsessive about.”

But even as a purely symbolic step, raising the status of Buddhism risks inflaming an ongoing Muslim insurgency in Thailand. “It’s going to make the situation in southern Thailand a hell of a lot worse,” argues Zachary Abuza, a terrorist specialist.

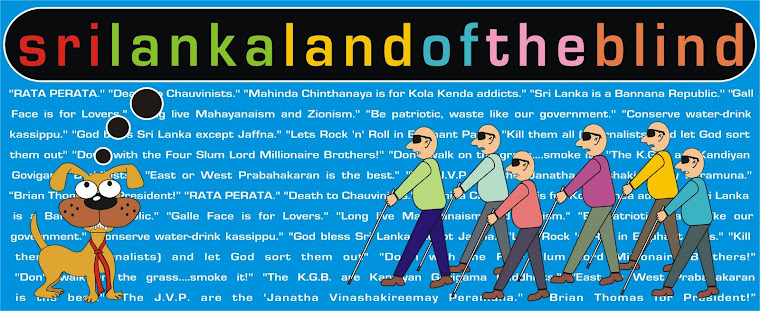

Thai monk Mettanando Bhikkhu warns his nation against following Sri Lanka, where Buddhist nationalists formed a political party, joined the governing coalition, and worked against peace negotiations with Tamil guerrillas. The Sri Lankan constitution provides Buddhism with the “foremost place” in Sri Lankan society.

Although many forces are to blame for Sri Lanka’s descent into civil war, Buddhist nationalism has inflamed the conflict. After decolonization in 1948, the Buddhist Sinhalese majority enhanced its position at the expense of the largely Hindu Tamil minority. The U.S. Agency for International Development reported: “The notion of the Sri Lankan nation subscribed to by many Sinhalese — including most of Sri Lanka’s politically influential Buddhist monks — is based on a firmly-rooted belief in the primacy of the Sinhalese/Buddhist majority and its culture.”

Buddhism has a special place in Sri Lankan politics; officials pay fealty to Buddhist clerics after assuming power, and the military has incorporated Buddhist rituals into its ceremonies.

Religious liberty remains tenuous even in areas far away from military conflict. Buddhist mobs, sometimes led by monks, have frequently attacked Christians, their churches, and their ministers. The authorities have been reluctant to arrest those responsible. With the constitutional sanction of Buddhism as a state religion as its guide, the Sri Lankan supreme court has ruled that proselytizing is not a protected religious activity under the constitution. (The jurists refused to recognize a Catholic medical group which, it declared, had provided an improper “allurement,” health care, to procure a conversion.)

Some Buddhist nationalists want more. Three years ago extremist monks formed the Jathika Hela Urumaya (JHU), or the Pure Sinhala National Heritage party, to promote Buddhist nationalism. The party has opposed negotiations to end the Sinhalese-Tamil conflict, which has cost tens of thousands of lives.

Although the JHU possesses only nine seats in the 225 member parliament, it provided important support for the 2005 election of the Sri Lankan president, Mahinda Rajapakse. The candidate agreed to an election program to revise the ceasefire and reject federalism as a basis for peace.

The JHU formally joined the government in January, boosting a narrow majority. The party’s influence likely ensures an even more bitter civil war. “Talk can come later,” says JHU’s parliamentary leader, about the peace process.

The JHU continues to press a constitutional amendment to institutionalize Buddhism, which has yet to come to a vote in parliament. The party also is pressing legislation that would ban “unethical” religious conversions. A similar bill has been approved by the Sri Lankan cabinet and was referred to a special parliamentary committee last year.

Thailand is not Sri Lanka. Adding a couple lines about Buddhism to the Thai constitution might have little practical impact. Sri Lanka, however, offers a dramatic warning: Buddhism and nationalism constitute a violent, combustible mix. Thailand’s military rulers should not toss aside their nation’s reputation for tolerance in pursuit of short-term political gain.

No comments:

Post a Comment